This was also published on the MattPlaysChess Substack. Join me there!

Last time, in Life in the Lowest Section, I wrote about what it feels like to play in the lowest section of a chess tournament — the noise, the kids, the nerves, and the sense that anything can happen.

This time, I wanted to find out why it feels that way. Are ratings in the lowest section really as meaningless as they seem?

If you’ve ever played in a under 1000 section, you know the uncertainty. You see the pairings, check the numbers, and make an assumption — I should win this — only to be completely wrong ten moves later. Either your opponent plays like they’ve been training with Magnus, or you realize you’ve just blundered a piece for no reason.

So, I went looking for evidence. I gathered data from about a dozen USCF tournaments that took place in October 2025 — weekend open events with Swiss pairings and at least fifteen players in the lowest section. Then I calculated a performance rating for every player: how strong they actually played based on their opponents and their results.

The idea was simple — compare tournament performance to each player’s pre-tournament rating and see how close the two really are.

What I found confirmed what everyone in the bottom section already suspects: down here, ratings are more like works in progress than fixed truths.

How Ratings Are Supposed to Work

A chess rating is meant to describe your current level of play — a number the system uses to predict how you’ll perform. You can read more about the Elo rating system if you are interested or USCF’s version of the Elo system if you are really interested.

If you’re 100 points higher than someone else, you’re expected to win about two-thirds of the time. Over many games, your rating and results should match up. If you exceed those expectations then your rating goes up more.

That’s how it works in theory.

In practice, especially in the lowest sections, ratings lag behind reality.

A “700” might be a new player just getting comfortable with basic tactics, or a kid who’s improving so fast that the system can’t keep up. Ratings are supposed to represent stability, but in the lowest section, nobody is stable yet.

The rating system isn’t (totally) broken — it’s just trying to measure a moving target.

How I Calculated Performance Rating

Every USCF crosstable lists who each player faced, their opponents’ ratings, and their results. From that, I computed each player’s performance rating — an estimate of how strong they actually played that weekend. If you want to learn more about performance rating, you can learn about that here.

It’s not perfect, but it’s consistent the board.

I ran that for every player, about 900 in total, in both the lowest and highest sections of twelve October tournaments, giving me a side-by-side view of how predictable — or unpredictable — the rating system is at different levels.

Ratings vs. Performance

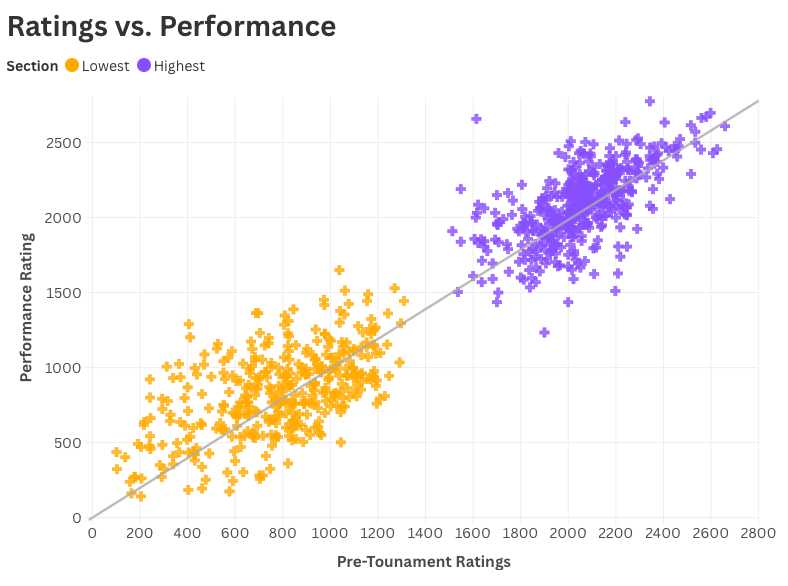

Each mark in this chart is a player.

The diagonal line shows where performance and rating match exactly — the place where expectations meet reality.

In the top sections (purple), the dots stay closer to the line. Ratings and results agree; experience smooths out the randomness.

But in the lowest sections (orange), the pattern dissolves. A few players rated 400 performed like 1300s. Others near 1000 played more like 500. The points scatter into a cloud that barely remembers what a line looks like.

It’s a clear visual: at the top, ratings predict results. At the bottom, they chase them.

How Far Off the Ratings Were

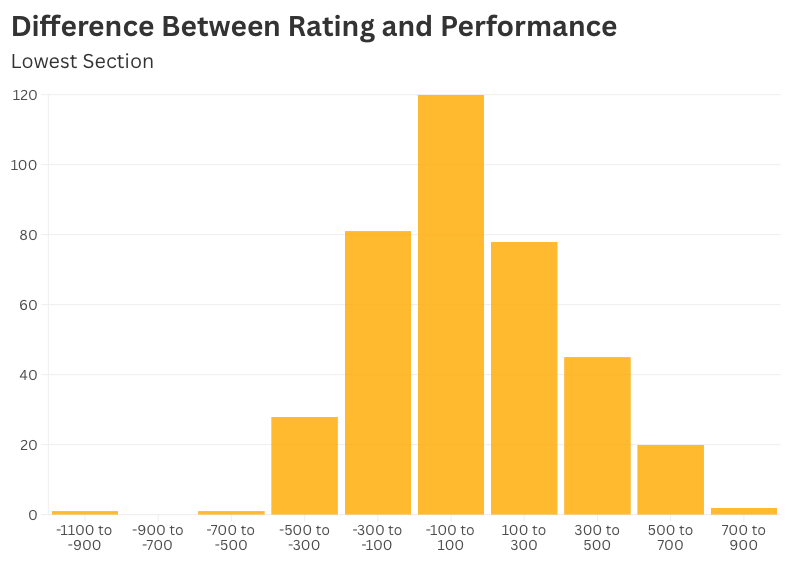

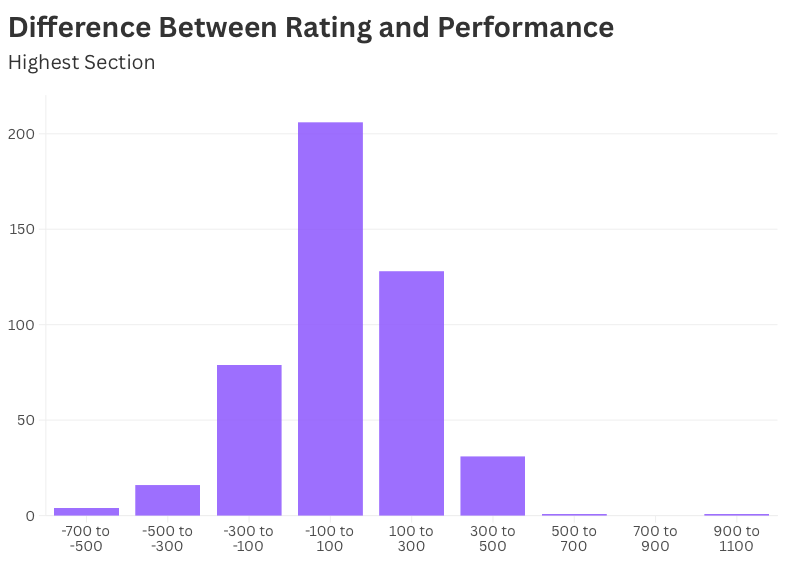

If the previous chart shows where everyone landed, these histograms show how far they drifted from where the system thought they belonged.

At the top, most players’ performance stayed within a hundred points of their rating — small fluctuations that even out over time.

At the bottom, it’s a different picture. The spread is wide, and the outliers are extreme. Some players performed hundreds of points better or worse than their rating. A few over-performed by 800 points in one event.

That’s why the lowest sections feel so unpredictable: you’re not playing against someone’s rating — you’re playing against their trajectory.

The Wild West of Unrated Players

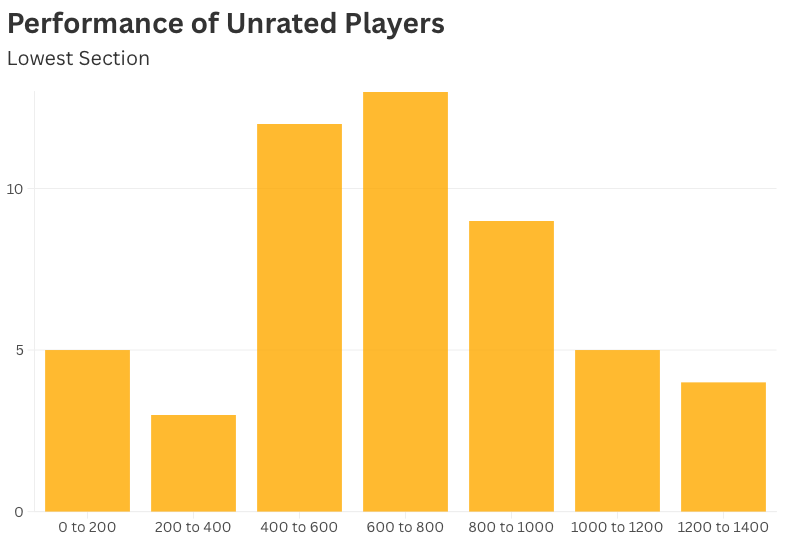

And then there are the unrated players — the blank slates. There were over 50 in the tournaments I looked at.

Their performance ratings ranged from under 100 to over 1300. Some truly were beginners; others were experienced players finally joining the rating system. For USCF, it’s an impossible guessing game — the first few events are just calibration.

Facing an “Unrated” opponent is like flipping a coin: one side is a new player still learning notation, the other is someone who’s been studying openings and endgames for months and just never bothered to enter a tournament.

What It All Means

In my last article, I wrote about what it feels like to play in the lowest section — the tension, the noise, and the sense that anything can happen. You can read Life in the Lowest Section if you missed it.

These data show why it feels that way.

The ratings don’t tell the full story. The section might say “Under 1000,” but that doesn’t mean you’re facing players who are truly under 1000 in strength. Some of them are already playing at the level of 1200 or 1300 — their ratings just haven’t caught up yet.

That’s what makes progress here so difficult to see. You can play well, lose to someone rated 600, and walk away with a lower number next to your name — even if your opponent’s actual strength was twice that. The rating system isn’t wrong; it just hasn’t had enough data to figure everyone out yet. But for players trying to measure improvement, that lag is discouraging.

In the lowest sections, you’re not just playing chess — you’re playing through uncertainty. Every opponent is somewhere on their own curve of improvement, and you only find out where when the clock starts.

That’s the real challenge of this level. It’s not only about blunders and tactics; it’s about learning to play well even when the numbers don’t make sense.